Howard Terminal History

For more information on the present and future, please visit the Bay Area Council’s economic impact study: http://www.bayareaeconomy.org/report/economic-impact-of-howard-terminal-developments/ . On to the past:

Introduction

Introduction

Welcome to this very longwinded history of Howard Terminal. Howard Terminal is located on the Oakland Estuary, between the Port of Oakland’s major container facilities and Jack London Square. The Port of Oakland currently uses Howard Terminal for the staging of trucks and storage.

The proposed plans include building a ballpark within a park, which, in addition to building the ballpark, would increase green space, waterfront access, and recreational opportunities at the Port. This history recounts how the site became what it is and might inform decisions for its more productive use and access in the future. This history will start with the early industrial development at the Port in the mid-1800s and go from there.

The Early Estuary

The Early Estuary

Like much of the Bay Area—the early waterfront consisted of mainly wetlands, tidelands, and marshlands. Situated on the San Antonio Creek, these areas were apart of vibrant ecosystems and home to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. In the early to mid-19th century, settlers came to the area in the lead up to the gold rush. This influx of population and business prompted California’s incorporation as a state.

When the State of California was incorporated in 1850, it gained control of navigable waterways to keep them for public use and access through a Common Law principle known as the Public Trust Doctrine. The new State of California now owned both the Oakland and the San Francisco waterfronts.

At the point of California’s incorporation, the control and uses of Oakland’s waterfront and San Francisco’s waterfront began to diverge. Shortly after California gained control of the East Bay waterfront, the new State of California allocated the waterfront to the Town, and eventually, the City of Oakland. This allocation was to promote private development of the estuary's Oakland side while preserving state funds. In contrast, the State retained control over San Francisco's waterfront using state funds to promote its own uses.

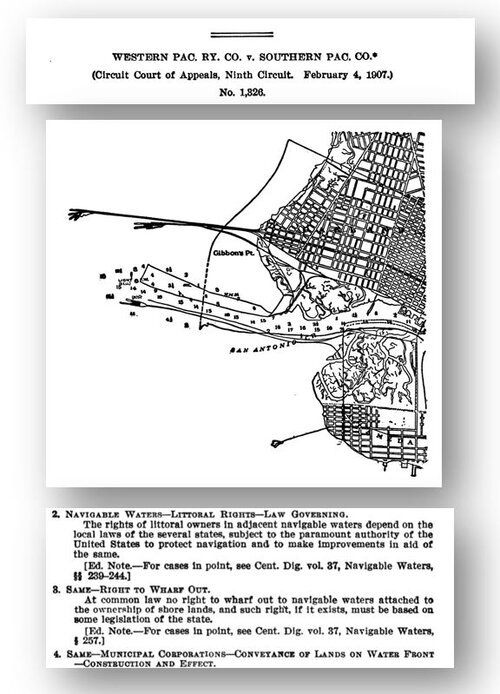

The original grant of the Oakland waterfront occurred in 1852 when Horace Carpentier founded the Town of Oakland. In backroom deals, mostly hidden from the public that didn’t even know of incorporation, Carpentier deeded himself the entire waterfront in exchange for building a dock near Broadway Street. Carpentier used this deed to sign multiple long-term deals, leasing much of the waterfront to the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Though the Southern Pacific Railroad brought new business and opportunity, some citizens rebelled. Many Oaklanders sought to take separate parcels of land in individual legal disputes. Alternatively, figures like the author Jack London and the oyster pirates would clash on the estuary with the Southern Pacific Railroad. In these skirmishes, the oyster pirates took down the Southern Pacific Railroad’s fences and bridges in protest. In fact, The First and Last Chance Saloon, a bar now located in Jack London Square, paints a picture of these early years and the bar itself is on top of one of these old oyster pirate boats.

This early era of unrest at the waterfront ended in the early 20th century. A court case in which the Western Pacific Railroad successfully wrested control from Carpentier and the Southern Pacific Railroad concluded in 1907, which for the most part ended the main disputes around Oakland’s waterfront in the second half of the 19th century. As this era of unrest came to a close by the early 1910s, there was a new era of stability to the waterfront, which now had both railway connections and sufficient outgrowth of the waterfront area.

In this era, the City of Oakland became more connected to its waterfront. The City, and eventually the Port of Oakland, began to consider Jack London as a symbol of Oakland’s spirit. He represented grit, resilience, a willingness to protest. As an actual symbol of this era, Jack London would not physically come to the Port until later in the 1950s, well after many of his adventures and famed writings were published. However, by the turn of the century, now freed from Southern Pacific Railroad and State Control, Oakland and its waterfront were finally in control of its own destiny. This freedom contrasts to its rival waterfront across the bay in San Francisco, where the state-controlled that waterfront until 1968 with the Burton Act's signing.

The Howards

The Howards

In the period of stability following the railroad saga, what is now known as Charles P. Howard Terminal became a focal point of Oakland’s energy and shipping industry in the early 20th century. It was a site of both progress and innovation throughout its existence at the Port. John L. Howard, the father of Charles P. Howard, was the original builder of the docks. John was the president of the Western Fuel Company, located at the site of what is now Howard Terminal. The site was previously home to the Oakland Nail Works factory, which was in use in the late 1800s until the warehouse was damaged. The Howard Terminal site was home to a new company formed by John in the early 1900s, which imported coal from around the world and places like Australia, England, Wales, China, and British Columbia to the Bay Area. The Oakland Gas Company, one of the predecessors to Pacific Gas & Electric, then used imported coal to make gas.

East Coast entrepreneurs often ventured west seeking a new opportunity. Of these early days, Bruce S. Howard, grandson of John and eventual board member of the board of the Howard Terminal Company, described the origins of the site’s formation:

“They came from the Philadelphia area, and probably in the 1860s…. My grandfather [John L. Howard] was involved in the coal business in Vancouver Island, and later that interest and involvement brought into the purchase of a piece of property at the foot of Market Street in Oakland. I remember my father [Charles P. Howard] telling me this story, that as a thirteen year-old-boy…My grandfather proudly showed my father this piece of property, which was half under water, covered with debris, from an old company called the Oakland Nail Works. My father came away trying to be respectful, but scratching his head, thinking what on earth his father had in mind for this.”

In 1902, that piece of land became the Howard Terminal, which was established as part of the largest coal distribution terminals in the Bay Area. Coal was imported put into bunkers and railcars for distribution to different industries around the Bay Area.

In addition to his various business ventures, John Howard served on the Oakland City Council in the early 1900s. He left the City Council to travel internationally for business. However, in his resignation letter to the city, he expressed interest in participating in a parks project in Oakland. He praised New York’s Central Park and stated that Oakland should build a similar place for recreation. In his letter to the mayor, he stated that “one cannot help admiring the wisdom and foresight in providing such a place for the teeming population of this city [Oakland]. We should be wise now for future Oakland.” This vision for a park would eventually parallel the vision for Howard Terminal that emerged later in the 1960s and 1970s.

After almost a decade of operating the coal to gas company, John sold the business's energy portion, the coal to gas company, to British Investors in 1910. At that point, the company moved from energy to more general shipping and logistics and became known as the Howard Terminal Company. Coal remained an import of the terminal until 1918 when it added more general cargo to its operations. The shift was in response to a transition from coal to oil to serve energy needs.

In 1913, John added more transportation infrastructure the terminal. This infrastructure include a railroad built to assist with distribution in 1917. With three miles of tracks on the 16-acre facility, the Howard Terminal continued to import and distribute products to the East Bay.

Three generations of Howards worked at the Howard Terminal, John’s son Charles and eventually Charles’s sons Harmon, Bruce, and Peter. Charles took over the Howard Terminal Company in 1920. Charles updated the wharves to support the new shipping and distribution industry for offloading, warehousing, and storage.

Howard Terminal preceded the Port of Oakland by more than 20 years. At the time, it was at the forefront of marine shipping logistics. Coal would be offloaded by hand trucks and put in transit sheds and warehouses. As the ships became heavier, the docks were updated to provide deep-water port capabilities. After 25 years of private operations at Howard Terminal, the Port of Oakland was established in 1927, becoming an independent department within the City of Oakland’s government. The Port of Oakland would lease terminals to tenants to seek additional tonnage and allow some terminals, like Howard Terminal, to remain privately owned.

Throughout the Great Depression and World War II period, Howard Terminal maintained good business, expanding its operations. During the war, much of the Howard Terminal inventory transitioned to military supplies serving the Pacific theater. There were so many supplies to move out of the Port of Oakland that steamships were seized by the government and used for supplying troops. The supply levels were increasing at such a pace that Charles Howard had difficulty keeping up with the demand and finding employees to work at the terminal.

After the war, Howard Terminal shifted almost entirely from energy and military supplies to grocery materials. With the rapid expansion of grocery products coming into the Bay Area after World War II and into the 1950s, Howard Terminal expanded its warehouse and trucking business. This expansion marked a departure from the previous railroad use at the terminal and largely mirrored shipping’s shift from rail to trucking in the post-World War II period.

Howard Terminal built new warehouses around Oakland and used them to store products for companies like Campbell’s Soup and Pillsbury. At that time of expansion, the terminal employed as many as 350 people. Eventually, the Howards sold the business's warehousing and trucking sides to the Hazlett brothers of the Hazlett Warehouse Company in Oakland. Despite the sale of the downstream logistics side of the company, Howard Terminal remained in the family. It continued to operate at a smaller scale, using much the same loading, offloading, and warehousing technologies developed in the first half of the 20th century.

At the time in the 1950s and 1960s, coinciding with the sale of the business's warehousing and trucking sides, two opposing movements were occurring at the Port of Oakland. These two movements were the expanding role of conservation, recreation, and access through Jack London Square's development on one side and the Port of Oakland’s shift towards new containerization technology at the port on the other side.

Both of these movements were affected by one of the most influential figures in the Port of Oakland’s history, Ben Nutter, Executive Director of the Port in the 1960s and 1970s.

Containerization and Oakland's Shipping Revolution

Containerization and Oakland's Shipping Revolution

The rise of containerization and the shift from European markets towards Asian markets drastically changed the shipping industry and led to Oakland’s renaissance as a major North American shipping center. Long in the Port of San Francisco's shadow, the Port of Oakland was a disruptive force in pioneering the new methods of container shipping.

The Port of Oakland was able to implement containerized shipping much more quickly than the Port of San Francisco. There were two major reasons why San Francisco was slower to implement containerization. First, unlike Oakland’s waterfront, San Francisco’s waterfront was still controlled by the State of California. The City of San Francisco didn’t have full authority to coordinate their industry with new shipping companies. Second, San Francisco’s ports were older and supported by pilings that could not adequately support larger containers or cranes. Due to these constraints, San Francisco maintained use of older technologies and therefore began converting its waterfront to more commercial and less industrial or shipping uses. Oakland had plans to convert its waterfront for both commercial and shipping uses; however, containerization's arrival created opportunities that outpaced the commercial developments. Many of these opportunities were uniquely tailored to the Oakland waterfront.

Containerization took root in Oakland because of a series of events and opportunities that led to two western shipping companies, Matson and Sea-Land Services (later acquired by Maersk in 1999), and numerous Japanese shipping companies to choose the Port of Oakland as the base of their new container operations.

Containerized shipping first appeared when Malcolm Purcell McClean, who eventually would start Sea-Land Services, thought of this technology as the next phase of globalization and cheap transportation of goods (in the 1950s). He shifted operations on the East Coast to containers. The new method of using containers made shipping much larger volumes of goods, up to 25 times cheaper. As McClean was pioneering this technology on the East Coast, West Coast containerization efforts were stagnant.

Containerized infrastructure did not have a large presence on the West Coast until 1962 when McClean introduced new East to West Coast shipping routes and sent to the Port of Oakland a containership that was one of the world's largest: the Elizabethport. This trip was met with much fanfare and celebration at the Port. The Port celebrated the September 27, 1962 arrival of this new type of ship as “a rebirth”. Sea-Land Services then proceeded to sign an initial lease for container services with the Port of Oakland in 1962.

The longshoremen union saw the rapid transformation of the industry and moved from opposition to promotion after negotiations that took place in the late 1950s. After extensive discussion, The International Longshoremen’s and Warehouse Union and the Pacific Maritime Associations (representing shipping companies) came to an agreement. This agreement set a baseline for working hours and created the Mechanization and Modernization fund, which was a tool to equally distribute the benefits of this technology to both workers and shippers.

To implement this new technology, the Port needed capital to build massive new facilities for the new shipping method. Containerization led to fewer, bigger ships. As these ships got bigger, ports needed to be deeper and cranes needed to be larger, which meant Oakland needed big facilities in more open parts of the Port. To raise money through voter-approved bonds to build these new facilities, the Port needed big shipping companies to sign long-term preferential leases.

Prompted by military transportation needs in the South Pacific, the first of these long-term leases came in 1966 with McClean’s Sea-Land Services, almost four years after the entrance of the Elizabethport and signing of the initial shorter-term lease.

Containerized shipping provided supplies for the military. However, on the way back to the Bay Area, ships would stop in other countries to pick up goods. New routes created a demand for shipping between Asia and North America, which prompted other shipping companies to enter the market. Following Sea-Land Services, Matson, anticipating rapidly expanding business with Asia, sought to move to Oakland from Alameda. With the Matson lease, the port needed to even further extend, in this case, to the 7th Street Terminal.

Executive Director of the Port of Oakland Ben Nutter was heavily involved with the funding and expansion of the port. Aside from voter-issued bonds, there were two other sources of growth. These were the BART Transbay tube project and the Economic Development Administration.

The Port negotiated to issue an easement to BART in exchange for a series of services to make way for the new facility. One service was the demolition of an old wharf reverting to the city from the Carpentier days. BART would also facilitate structural work by using the materials from digging the BART tunnels to fill the wetlands where the new facility would be.

In addition to the BART project services, the Economic Development Administration issued Oakland a grant to help build the new facility under the Federal Department of Commerce. Despite some early disagreements between the Economic Development Administration, the Port, and Matson, the facilities were eventually completed. Matson signed a long-term lease—making Oakland the hub of its new containerized Asia operations.

This almost doubled the Port of Oakland's capacity, making it one of the premier shipping hubs in the Pacific Ocean. Much like the initial entrance of the Elizabethport into Oakland, the dedication of the 7th Street Terminal was a city-wide event drawing six thousand people for tours.

“Cities have traditionally grown where means of transportation meet.

For this reason, there was never a better place for a city than Oakland, at the hub of the Eastbay- and indeed the Bay Area.

The Eastbay was destined by nature to be a shipping center.”

-Oakland Tribune

In addition to negotiating the port's expansion to the 7th Street Terminal, Ben Nutter also acted as a diplomat for the Port, gaining new trade partners, specifically in Japan. In 1963 and 1965, Nutter was part of a delegation to Japan that solidified new relationships. In 1966, Japanese delegates visited the port to inform the construction of Japan’s containerized ports. These new relations culminated in an agreement with four Japanese shipping operators choosing Oakland as their hub at the new 7th Street Terminal, all of them signing preferential leases and sharing the space with Matson. These deals were the starting point of high new trade routes between Oakland and Japan, which would create a six-fold increase in trade between the United States and Japan between the opening of the facility and 1980.

Moving into the 1970s, containerization at the Port of Oakland had disrupted the landscape of shipping in the Bay Area and North America. What used to take dozens of longshoremen a week to do could now be done by less than half of the in one business day. Much like other industries like computing, the internet, or biotechnology in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Bay Area was on the cutting edge of new technology. Oakland pioneered this technology for the West Coast. This resurgence created an image of the Port of Oakland as a resurgent innovative force. The City, aware of these achievements by the Port, celebrates this history and shares it with its citizens. The Port's cranes came to represent the growth and transformation of the Port and the City of Oakland.

However, this technology shift led to port activities' centralization to only those sites that could make this leap to more advanced loading and off-loading. Because of resource and space constraints, economies of scale led to larger vessels and more concentrated and consolidated facilitates. This led to a retraction of port activities that increased productivity and decreased and altered the footprint of ports.

Facilities that could not negotiate leases or invest in new mechanized cranes were abandoned. Abandoned facilities were in areas where they could not build new facilities. High up-front cost and capital-intensive projects were being built in other, more open areas of the port due to new large containership demands.

The effects of these massive projects and investments quickly came to Howard Terminal. As containerization was progressing, older, privately-owned terminals further nestled in the estuary, such as Howard Terminal, faced a decision of either scaling operations to match the new facilities or pivoting to new business models and potentially new visions for the space.

Jack London Square and Oakland Environmentalism

Jack London Square and Oakland Environmentalism

At around the same time as the first signs of containerization in the early 1950s, a parallel development occurred in the Bay Area. The conservation movement and a broader reconnection with Oakland’s conservationism took root at the Port with both Ben Nutter and with the Howard family.

In 1950, the Port of Oakland created a new commercial area with restaurants and attractions to honor the port's history. The area was named after the very embodiment of grit and frontier mentality before Oakland successfully reclaimed the area in 1907: Jack London. Jack London’s adventures in the Yukon and eventual writings on nature and wilderness had inspired the nation.

The City of Oakland was enthusiastic about adopting Jack London as one of its symbols. A Coast Live Oak tree was planted by City Hall at Frank Ogawa Plaza in 1917 in his honor. Then-Mayor John Davie stated that the tree would serve as a symbol and a “sturdy sentinel [that] may stand in memory and honor to Jack London”. Despite this broader connection to Oakland, the Port’s connection to Jack London ran deeper than the rest of the City.

Jack London Square was established as a new attraction as the Port. Ben Nutter appreciated Jack London’s memorialization of the Port’s early history as well as the symbol of its spirit. In pursuit of more attractions and solidifying the new area as the center of this philosophy, Nutter negotiated to bring Jack London’s Yukon cabin to the Port. When confronted with the fact that the Yukon delegates didn’t want to give up the cabin, Nutter and his associates comprised, proposing that the cabin be deconstructed log by log and split between the two places. Characteristic of the negotiating skills of Nutter and others at the Port, half of the logs were brought to the Port and half remained in the Yukon. The cabins were then rebuilt using alternating original and new logs. That piece of Jack London’s frontier spirit remains at the Port today, with a bronze statue of Buck from the Call of the Wild.

Simultaneously, as Jack London Square was developing under Ben Nutter, the culture of conservation in the Bay Area was changing. Concerns around access to the waterfront and recreation were increasing, as was the desire to avoid further wetland damage.

In 1965 the McAteer-Petris Act was passed, creating the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, which oversaw new development and infill of wetlands in the Bay Area.

Additionally, institutions like the Audubon Society and other conservation groups sought to further protect wildlife and access to areas around the Bay Area. New development became more difficult, and restoration of lost wetlands became a priority. To coincide with these new attitudes towards access and development, many in the movement naturally felt that more protected waterfront areas and recreational areas like Jack London Square would make better use of the space and protect the remaining fragile wetland ecosystems. Naturally, tension began to develop with the growing port, and competing visions for the waterfront area emerged.

The Howard Family also became more involved in the conservation movement. While the Port was rapidly expanding, both Charles and Bruce, now a board member of Howard Terminal, became increasingly involved with the Save the Redwoods League.

Redwoods are an integral part of Oakland’s history. The old-growth redwoods in the Oakland Hills used to be so tall, that they served as shipping markers. These trees provided many resources while the Bay Area was being built. This deforesting prompted local groups to save the old-growth trees, essentially creating a local conservation movement. This effort led to the establishment of the East Bay Regional Parks District during the depression, leading to California becoming the first state to create a regional parks district. The East Bay Regional Parks District and Save the Redwoods League worked together to preserve these redwood forests since the 1930s. Unfortunately, the old-growth forests were already logged by that time, and now there is only one of these old-growth redwoods in the Oakland Hills named Old Survivor. However, the legacy of conservation has led to the regrowth of many new redwood trees throughout the Oakland hills.

Continuing this Oakland legacy, Bruce Howard served in many leadership roles in Save the Redwoods, eventually becoming its president. While Bruce was a director and Charles was a council-member of Save the Redwoods, the group was instrumental in creating Redwood National Park in 1968. With them, figures like Horace Albright and Walter Haas Sr. sought to protect many acres of redwoods and provide access.

Eventually, in 1980, Bruce Howard would serve as President of the Save the Redwoods League and briefly serve as an interim board member of the National Audubon Society. He would coordinate with other organizations like the Peninsula Open Space Trust and Sempervirens to further access and preservation efforts. Under Bruce’s presidency, Save the Redwoods was instrumental in protecting many redwoods around Northern and Southern California.

This shift towards advocating for the expansion of lands for recreation was similar to the new vision of Howard Terminal. Confronting both the disruptive forces of containerization and the constraints around the location of the site within the estuary, Bruce opted to shift the vision of the site in the late 1970s, wanting to create a new Jack London Square area. This would effectively expand the commercial and residential access to the Howard Terminal area's waterfront and bring back John Howard’s vision and enthusiasm for more recreational space in Oakland.

However, this idea placed Bruce’s vision and Ben Nutter’s vision of protecting Oakland’s new status as shipping of the Pacific Ocean squarely at odds.

Opposing Views at Howard Terminal

Opposing Views at Howard Terminal

Both Bruce Howard and Ben Nutter had a balanced approach to business, environmentalism, and using space at the port. Bruce was appointed to the State Highway Commission by Jerry Brown because he was, as Bruce described, “a businessman with environmental bent”. Ben Nutter was aware of the trade-offs associated with Port space, stating, “each port project and its site’s competitive uses must be weighted and decided on some rational basis. We must have ways to comprehend and compare competitive use values”. Both knew that the Port would eventually have to determine where recreational uses would end to give the Port space to grow. However, they disagreed on where.

As some facilities further in the estuary were deciding not to invest in container infrastructure, the Port was looking to expand. Bruce later stated, “we got the first inkling that the port was looking to expand their inner-estuary container facility.”

However, Bruce thought the property would be more beneficial as a commercial area with more space for recreation and access. When asked if he wanted to make another Jack London Square, Bruce said “that’s right that’s what Harmon, and I wanted to do, but the Ports had other thoughts”.

How much space and how many facilities the Port needed for the new container projects was unclear in the late 1970s; however, Bruce knew they didn’t want to containerize Howard Terminal as early as the 1960s. The investments required and the general use of the space in that manner weren’t Bruce’s vision of the site.

Ben Nutter and the Port generally, however, couldn’t know what the new technology at the Port would require and did not want to mortgage any potential space needed to solidify Oakland’s successful container shift further. The Port always had the power to condemn the site through litigation but never used it with Howard Terminal. When it was clear that alternate recreational uses might foreclose opportunity, the Port opted to send a letter asking for negotiations instead.

On the recommendation of Charles, Bruce and Harmon negotiated the sale of the terminal to the Port. The Port was able to maintain the potential space for the new container operations in case it need it to secure their foothold in the Pacific shipping industry, and Bruce and was able to go on to oversee the Save the Redwoods League.

As a tribute, the Port named the large area around its newly owned terminal the Charles P. Howard Terminal.

Howard Terminal Post 1980

Howard Terminal Post 1980

Since the sale of Howard Terminal, the Port has seen growth in its container business and at Jack London Square. Howard Terminal eventually became, and still is, an area for storage and staging for trucks moving in and out of the Port.

Sources and Further Reading

Sources and Further Reading

University of California, Berkeley Library History Department

Local Wiki

Alexis Madrigal’s fantastic podcast and posts on containerization (also check out his new book The Pacific Circuit)

The Rise of Maritime Containerization in the Port of Oakland 1950 to 1970 (2000) by Mark Rosenstein